This was a time for action; a time for leadership.

And so we made this:

|

| The 'Weekly Stuff' Chart- regularly featuring threats, as seen in the upper left-hand corner. |

'Weekly Stuff' chart. A project spearheaded mostly by myself.

The concept is fairly simple: each week, each person will be assigned one of 6 tasks. They perform their task for the whole week, and if they don't, we shame them.

"Kitchen" meant doing the dishes and straightening everything else in the room to keep it clean.

A few of these are self-explanatory.

|

| Eggs- 'community food' in dorm 232. |

|

| Most types of food remain individually owned and labeled. |

The Weekly Stuff Chart yielded some interesting results. Most notably, the amount of milk, eggs and bread consumed skyrocketed. When I served as our first milk man, the dorm got by on 3-1/2 gallons of milk just fine, but by the time Peter had gone for milk a few weeks later, we were barely getting by on 5 gallons. Our first egg-buyer brought 36 eggs to the dorm to last his shift, but it wasn't long before we had managed to consume 108 eggs in a single week. Bread was disappearing by the loaf, and the job of community food purchaser became a burden indeed.

Why did this happen?

Microeconomic theory holds that people will weigh the costs and benefits of their actions when determining what to do. It holds that people are economically rational, meaning that they will arrive at conclusions that maximize their personal advantage.

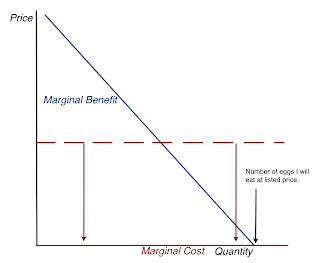

Suppose I decide to eat eggs. To determine how many eggs I will eat, I measure the marginal benefit and marginal cost of eating eggs. The marginal benefit is the benefit I gain for each additional egg I eat, and the marginal cost is the price I pay for each egg eaten.

The law of diminishing returns states that as I continue to eat eggs, they will gradually give me less benefit. After all, food tastes better when you're hungry, so it stands to reason that it will be less tasty to me as I start to fill up. Furthermore, as I eat eggs I will eventually get sick of them and desire variety, so in that sense they will also become less pleasurable.

Whatever the cost of eating eggs- it isn't going to change, per egg, as you eat more eggs.

This is represented by Figure 1-- a static marginal cost line, and a downward-sloping marginal benefit.

|

| Fig. 1 |

The thing about eggs is that if I eat one, it's gone. Same goes for milk, if I drink a glass, or bread, if I eat a slice. Thus, if I'm the one buying, the marginal cost of these items is the knowledge that if I want it again, I'm paying for it myself. The more I have to pay, the higher the total cost.

It shouldn't be hard to see then how the concept of community food changes the graph-- marginal cost goes down. After all, if I eat an egg with the knowledge that somebody *else* is replacing it, it's no longer such a big deal. The cost of eating an egg is now essentially zero, a change represented by figure 2.

|

| Fig. 2 |

As you can see, the quantity consumed has increased drastically, and for a relatively simple reason: if it costs me less to get the same thing, I'm going to get more of it. Note that in each case, the quantity of eggs (or milk or bread) is represented by the point at which the marginal benefit is equal to the marginal cost. This is because, rationally speaking, I'm going to keep eating eggs as long as the benefit outweighs the cost. Since the cost of eating eggs is close to zero in the case that they are community food, it stands to reason that I will continue to eat them until they cease to provide me any benefit at all (e.g. I'm totally sick of them).

Though unseen, this graph displays results that were fully realized by the members of our dorm as time went on. It then begs the question- is there a problem here? After all, what's wrong with eating more eggs and more bread if they're all being eaten?

The answer is yes, there is a problem. Because we're buying and consuming a lot of food that people don't actually want.

Even though the marginal cost *to me* is zero for eating another community egg, *somebody* had to go out and buy that egg, and the cost is imposed on them. When it's the egg man's turn to go out and buy 100 eggs for 8 dollars, only to have many of them be eaten by dorm members who barely want them at all, who end up valuing the lot at 5 dollars, he (the egg man) has performed an action that is of net loss to the dorm. It is rational for him to buy the eggs, because the rest of us have made sure to impose shame at a cost much greater than 8 dollars if he doesn't, but the end result is an irrational waste of resources.

This is a concept that no one else in the dorm fully understands, but the idea that massive community food expenditures like the ones we've been having probably aren't efficient is an idea that's resonating.

Much to the dorm's displeasure, other aspects of the Weekly Stuff chart fared badly as well.

|

| The typical state of our sink, on a good day. |

|

| Also a good day. |

Kitchen man rarely did the dishes, and the tables were exactly as messy as before. This is due to a couple problems:

1. The person who uses a dish or leaves out a mess is not the same person who has to clean it, meaning that dorm members have very little incentive to be resourceful about the messes they make.

2. There's only so much we can do as a group to inflict shame. We're not the government, so locking people up in jail or shooting them with a gun is off the table. This means on any given day that kitchen man is a little busy, if spending the time it takes for him to clean the amazing amount of mess six people can create in a kitchen costs more than the shame we can inflict, the messes will not be cleaned.

|

| "Passable." |

The refrigerator-- though technically the duty of kitchen man to straighten, was often disorganized and at oftentimes a complete mess. This brings to light another issue with community rules, which is that they are often hard to define. A "clean" refrigerator means one thing to someone who came from a house of perfectionists, and something entirely different to he who came from a house of chaos (you know who you are).

It is the nature of community jobs to be done to a bare minimum. Whatever one can get away with to avoid the consequence of shame.

|

| "Highly questionable." |

When it was suggested that perhaps Kitchen man simply had too much to do, we tried to divert work away from him and encourage a little personal responsibility through the creation of the "community standards" page (shown below).

It details the process by which people are supposed to aid in dish washing and pick up to a certain degree. Kitchen man is still to do most of the work, but everyone should do their part with regard to their own things.

Our system is crumbling.

The Solution

Privatize, privatize, privatize.

I venture that all of our problems stem from "community." The irony stings in knowing that I made the Weekly Stuff chart and now in my lonesome advocate its abolishment, but there are many other changes that need to be made for optimum efficiency in dorm 232.

Let's start with community food, and why we don't need it.

If you'll recall, the initial reasoning behind the institution of community food was:

"We determined that milk, bread and eggs would be consumed by all of us on a weekly basis, so rather than have us each making our own separate runs to the store just down the road, we could have one person do it for all of us."

This turned out to be irrelevant for 2 reasons. Firstly, the store contains a great many products that each one of us uses on a regular basis. Everything from toothpaste to paper is a must-have, and as it turns out, each one of us makes a run about once a week anyway.

Secondly, there is a perfectly good community-less solution that has already manifested itself on multiple occasions: compensation. For one reason or another somebody needs to pick something up but they're too busy to do it, and a quick exchange between them and another guy lying around who does have time ensures a speedy delivery. "Go pick this up for me and I'll pay for your laundry" is perfectly applicable to eggs, or bread, or milk should a dire situation ever arise.

When I most recently suggested we abolish community food, a new concern arose: fridge space.

Milk gallons, the dorm mate reasoned, were both spacey and popular to buy. If each one of us bought a milk gallon every week, we could never hope to fit them all in the space we had. After all, nobody wants to buy half-gallons, since the milk to dollar ratio is significantly worse.

A legitimate complaint, to which I devised a new solution.

Rather than label milk gallons individually, we could *co-own* them. Consider a milk gallon labeled like so:

Of the remaining 2,822 grams of milk left in this gallon, the labeling indicates that I own 822 grams of it, and some Jared owns 2,000. When we purchased this gallon, I must not have needed as much milk. I would have payed him an amount of money relative to the percentage of milk I owned after the purchasing, and whichever one of us picked up the milk from the store would have received a premium from the other.

The following process is then used when I choose to drink from our gallon of milk:

1. Use as much as I want.

2. Weigh the milk gallon when I'm done using it, and make note of how many grams of milk are left.

3. Make a brief calculation to determine how much milk I drank.

4. Adjust the label to reflect how much of the milk in the gallon I now own.

This solves the problem of over-consumption in milk, since the marginal cost for me to drink milk is equal to the marginal cost of buying the milk (I'm the buyer), and also ensures that limited fridge space is conserved for everyone to leave milk there. In fact, since milk consumption would be reduced to reasonable levels, fridge space taken up by milk would be reduced.

The reasoning used here should apply equally to eggs, which can be marked individually. Bread doesn't suffer at all from this problem, for obvious reasons.

When I proposed my solution again, bread was officially removed from the Weekly Stuff chart community food list. Eggs and milk is a work in progress, with complaints on the other side regarding the inefficiency associated with having to mark up eggs and milk so intensely before and after use. It remains obvious that leaving these foods to the community poses a far greater harm, but if any readers can think of a more efficient labeling solution, I'd love to hear it. I'm considering a couple other ideas myself.

Allocating Space and Capital

In dorm 232, as is typical with dorms everywhere, all space, other than the rooms, is treated as "community space." Strangely enough, it isn't even thought of in this manner-- it's just assumed as the way things are. I attribute this to the way people are raised in American households throughout their pre-college education, but there could be other, deeper factors at play. All the same, many problems are solved when this space is owned by individual members of the dorm.

It's worth noting, firstly, that some spaces *aren't* worth distributing to individuals. The hallways, for example, are so infrequently used that they aren't really "scarce." Exactly as often as people desire to use the hallway can they use it, and between the six of us there is never a "traffic jam." Just as there is no price on air, and nobody owns it, there need be no price on hallway use, or ownership thereof.

In dorm 232, as is likely typical of other dorms, there are a dozen significant sources of capital owned by the community.

1. Couch

2. Kitchen table

3. Refrigerator

4. Stove

5. Oven

6. Microwave

7. Kitchen Sink

8. Dishwasher

9. Shower

10. Bathtub

11. Toilet

12. Bathroom Sink

All of these should be owned individually.

Note that they can be divided up in many cases-- no one person has to own the entire kitchen table, and I anticipate that no one person would. If each of us has a strong desire for some table space, and none of us has a great desire for more than a small amount, the table would be divided six ways.

Since we can assume that, in a state of community ownership, each one of us owns each item of capital to an equal degree, simply bid off each item-- the highest bidder gains ownership and pays the rest of the community an equal portion of the determined price.

For example, I could call a price of $10 for the couch. If you value it more highly then 10, you bet $11. When someone finally ends with the highest bet of $25, he pays each of us 5-- his dorm mates-- $5 dollars, and then obtains ownership of the couch.

Some items, like the table, can be divided six ways right from the start (assuming 6 random portions of table are essentially equal in value), and then if one desires more table space he can buy it off someone who desires the table space less, if such a person exists.

Keep in mind that if I own the couch, I have an incentive to allow other people to use it, for a fee, during the times I'm not using it. So resources are unlikely to go to waste.

The kitchen sink would never be loaded with dishes, because you can't leave your stuff on someone else's property. To use the sink and dishwasher you would pay a minor fee, and then return it to cabinet space that you own.

Refrigerator space would be used wisely because you wouldn't have much of it, and, if you could fit the stuff you have in less space, you could sell of the unused space to someone who wants more and make money.

This is the way in which problems are solved.

So during the auction by which you will distribute all these utilities, wouldn't a student with a disproportionally large stipend end up owning the whole room if they so pleased and thus force his roommates into virtual sharecropper status? I'm not trying to poke holes in this argument; I'm legitimately wondering.

ReplyDeleteGreat post! Most entertaining. Your marginal cost/marginal benefit analysis is right on--an excellent illustration of the principle.

ReplyDeleteI do see some challenges to privatizing ownership of household furniture, though. How will you police that ownership? For example, if you aren't at home, how will you know if someone else is using your couch? And even if the couch-sitter agrees to pay, are you prepared to time the usage and then, when your customer hands you $20, make change for the $0.37 fee that might correspond to a 20-minute rental?

Private ownership of food has fewer problems, but for myself I never did it, and I always felt sorry for other dorms and apartments where refrigerators were filled with carefully labeled foods.

The machinery of the free market functions very well given adequate space--say a village or a city--in which to operate, and hundreds or thousands of people causing it to operate. But I wonder if that machinery doesn't become a bit intrusive in the close confines of a dorm, with at most six individuals trying to perform all its functions.

In your original argument, you mentioned that the original tool you used to impose costs on others for failure to do their jobs was shame. I wonder if that is the best method. Have you thought about good old-fashioned guilt? I don't mean guilt of the criminal or sinful variety, but rather the moral feeling of living in a system in which others are pulling some of your share. I am aware that this system does not work on a large scale, as proven by the USSR and other communist experiments. But it has been the way families, friendships, and small tribal communities have functioned for a long time. I wonder if it isn't a decent model for any tiny and close-knit group of people who share a common living space.

As an example, I share a driveway with an industrious neighbor. That driveway needs to be shoveled whenever it snows. If I don't get out and do it early, my neighbor invariably shovels it. He never says anything about it--I have heard him say that if I didn't live next door, he would have to shovel it anyway, so it's no skin off his back. This noble behavior causes me to feel guilty, so the next time it snows, I try to get out earlier and get shoveling. In the long run, things have balanced out pretty well, and the shared driveway has actually improved our relationship in a way that bidding or compensation could never do.

Conversely, in a prior house I lived next to an older couple. I shoveled my own driveway and sidewalk whenever it snowed, and then (since I was out there anyway) I shoveled my neighbors' sidewalk, and sometimes their driveway as well. The marginal cost was my time and effort; the marginal benefit was a smile and thankful word the next time I would see them. Seemed like a pretty good trade to me.

This works in countless other scenarios. I go to lunch with a colleague who offers to pay every time. If I know he paid the last time we went out, then I jump in and insist that it's my turn to buy. There is no tabulation and no keeping score--just a good, friendly relationship that benefits both parties and simplifies our dining experience.

There is a catch to all this: Someone has to start the virtuous cycle. The project doesn't work if the person providing the service expects a quid pro quo. And it doesn't work if he dwells too much on what he is doing. But if one person in your dorm were to start taking charge and doing other people's jobs for them, do you think it is possible that guilt would set in among the other residents? Would the deadbeats have a change of heart and start pulling their weight? Would the guilty party repent and pay the favor forward?

Are feelings of this particular brand of guilt unknown to the teenage mind? Or is it possible that the seeds of free cooperation are germinating just below the surface, ready to burst forth once they feel the warmth of industry shining from a selfless source of energy?

Cam: A perfectly good question, but keep in mind the overwhelming price of buying entire rooms. To buy out my half of my room, for example, including the bed, would likely have a similar cost to that of my rent. It's unlikely that anyone would want such a space at such a price, seeing as they have their own room, and their own bed, and the benefit gained by having a second bed is very slim.

ReplyDeleteThe kitchen would be yet more difficult, with a refrigerator, an oven, a sink, a couch and so much else, one person buying the whole thing would mean an enormous amount of cash for the rest of us-- and what use would he make of it? Why buy all the space in the refrigerator if your food fits comfortably in one-sixth? If you assume people are rational, which you do when applying economic theory, no one dormmate ever *would* buy everything in sight because he has little to gain and a high price to pay.

And if he did, for whatever reason, we'd take our cash and be perfectly ok-- pool together to buy a mini-frige and divide out the space through pricing, resort to more snack food and accept it as a good trade-off for the money we gained, and substitute whatever else as needed. If there's anything people are good at, it's substitution. Your use of the word "force" isn't sensible considering every trade is made with the consent of everyone involved. Whatever negative effects come as a result of losing ownership of the entire kitchen or whatever else, in your rather unrealistic hypothetical, will be weighed by the other five of us and considered as we come to an agreement regarding price.

Dad: Ownership has already existed without trouble in our dorm, and we certainly aren't feeling sorry about it. Like I mentioned in the post, the majority of food is already labeled individually, and never is it stolen. I think this has to do, in large part, with a general respect for property rights on behalf of everyone, especially Americans. Past this assumed respect we have only the powers of shame and guilt, but those can work as well with varying degrees of effectiveness. It's not perfect, but it works fine.

I don't see too much inconvenience arising in methods of payment. As is, pocket change is kept in abundance by the six of us- hidden away in drawers in our respective rooms- because the laundry machines won't accept anything else. I don't see it as too much of a difficulty to exchange dollars at the Wilk for a set of dimes when you're already going to pick up quarters, and dimes could be used quite easily for the majority of payments. Signs on privately owned couches and sinks would display rates such as "wash 3 dishes, leave a dime" or "relax for 10 minutes, leave 10 cents", and I expect that the trouble associated with shame, if you're caught, and guilt, even if you're not, would be more costly to the consumer than merely paying the modest fee.

The issue with using only guilt as a means to motivate people is that the problem extends beyond a lack of motivation. Our milk men are sufficiently diligent about *doing* their job-- to buy as much milk as people will drink-- but when they do that they buy milk wastefully. Ultimately, you aren't going to get a solution more efficient than what you can do with pricing, even if that means exchanging money rather than favors and having the little added cost associated with such. It seems to me that the bigger issue is a growing mentality that somehow it isn't nice-- moreover it's actually cold-- to charge prices and initiate voluntary trade that betters everyone.

So to answer your question, I think guilt is well known to the teenage mind, and could be implemented as an effective means of enforcement, but all the selflessness in the world won't allocate resources in a manner so efficient as the free market.