There is a lot of talk these days about rights, just as there was a smidgen over 200 years ago, when the founding fathers of the United States established a constitution to form a country of liberty. Politicians often stress the importance of “rights,” usually in describing how they intend to “preserve” them, but with so much talk come so many questions: what are rights? Where do they come from? Why do we need them, and where would we be without them? These queries are asked by the everyday Joe, discussed at great length by the most prestigious intellectuals in the country, and debated by the most powerful men and women in governments across the globe. In this article I strive to shed light on this important issue, and in particular I make distinction between the oft-confused concepts of “human needs” and “human rights,” to explain how they’re different, and why it matters.

The rights of everyone are two in number: the right to his person, and the right to the things he, as Enlightenment philosopher John Locke put it, “mixes his labor with.” These things are defined as his property, meaning that they can justly be used or traded away by their owner, and cannot be justly taken by other people. Rights are self-evident in the natural state of man, he being perfectly free to act independent of others, disposing of his possessions or his person as he pleases. This is important to recognize, as it means that no person is “given” his rights by other people; while some point to politicians and bureaucrats as the givers of our rights, they are, in fact, naturally inherited by everyone as a result of being able to make decisions. It is also important to note that one does not have the right to the possessions of others, or to another’s person, as nature does not grant anyone the power to control other people, or decide what those people do with the things that they possess. All rights stem from these two, basic umbrellas of what it is that people own. The United States Declaration of Independence famously declares the rights of its citizenry to be “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” the first of which is a logical conclusion of owning one’s person, and the latter of which are statements regarding the freedom of anyone to act as he chooses, provided he does not interfere with the rights of others. Man is incapable of creating new rights, but he is fully capable of taking them away.

But how does one take away the rights of another anyway? If nature bestowed our rights upon us, wouldn’t that mean they are impossible to revoke? Sadly, this is not the case. Unique to the actions of men is the use of force -- a physical invasion or threat of physical invasion that involuntarily bends the will of others to one’s interests. For example, a woman has the right, the option, to keep a purse she buys and use it to carry her things, this being the use of property she has honestly obtained. However, if a mugging man threatens her with a gun and demands her purse, he changes her options to: 1. give the man the purse or 2. get shot and lose the purse. Should the woman carry a handgun, she may choose to defend herself, this being a just use of force, but if she fails to oppose her aggressor or does not have such a weapon available, she will cease to have the right that nature has granted. In any other instance that the man approaches her without threat of such physical invasion, perhaps he approaches her with money instead and offers to buy the purse, the woman will always retain her right to keep her property. This is because any voluntary offer proposed by one human being to another will leave the offered person with the option to act as though nothing happened, and have no change to their circumstance. Thus, aggression through the use of physical violence is the sole destroyer of human rights.

Most commonly, people lose their rights to governments, oftentimes without even recognizing what has happened. It is the nature of a government to act in a manner that destroys rights, because it cannot exist without the use of physical violence -- this being the only way it obtains revenue. Consider a tax, and what that is and what it means. When the U.S. government taxes people, does it collect their money through voluntary agreement? Is it asking for donations to support a cause, or offering something in return? Indeed not -- the government demands each citizen pay his taxes, and threatens locking up in cages those who refuse to do so.

While it’s true that the government may provide services with tax revenue that may, in turn, bring benefit to the citizens who provided the funds, it remains as much a theft as the mugging man demanding the purse from the innocent woman. Even if he told her he would sell the purse and use the money to buy her a new coat, it remains a theft because he uses her property in a way that is contrary to her choosing. Even a government founded on democracy, with support from the majority of the people, will still destroy the rights of an oppressed minority if there is so much as one person who would prefer not to pay taxes in return for the benefits provided by the government, and typically it is many more than one person with such a preference. It is often said that in providing defense, the government protects rights and therefore is not destroying, but providing them. However, the distinction must be made between the rights of a people and the protection of those rights as, like many other things, nature does not provide protection to humankind. Furthermore, in order for the government to do so it must extract property from the citizenry by force, thereby violating the rights of taxpayers. While it’s also true that a citizen has the option to keep his things and leave the country, this violates the right of his person, his liberty in acting passively to remain where he moved to or was born without violating the rights of others. Because he has the right to both his person and his justly-acquired property, the government violates his rights by forcing him to choose between the two.

People are typically very fond of their rights, a truth that is self-evident and made manifest in pro-rights protests and movements across the world, and so governments will often remove the rights of a people by disguising their removal as the creation of a new kind of right -- the providing of one’s needs. Though “needs” are typically pretty hard to define, the basic understanding is that they are the resources and services that one requires in order to survive. The easiest way to see how rights and needs are fundamentally different, is while the former is provided by nature, the latter most certainly is not. Man does not live in a Garden of Eden, where food and immortality are provided by the goodness of natural law, he must act to receive his necessities, and by “the sweat of his brow” will he obtain the goods required to live. In other words, man can do nothing and retain his rights, but he must labor to attain his needs. When the government of China, for example, provides “material assistance” to the old, ill or disabled, under the guise of a right, what they are in fact doing is instating an obligation for other members of society to provide for these needs. As I said before, a government’s revenue can only be obtained through the threat of physical violence and the theft of other people, this because government by its nature does not produce wealth. The provision of this so-called “right,” therefore, is in actuality the removal of rights from taxpayers forced to provide for these material goods. Indeed, welfare or entitlement in any form, whether or not it is unjustly disguised as the provision of a right, is always destruction of the rights of innocent citizens.

This practice is used by governments all over the Earth, by some more than others. In 1945, the United Nations established a list of “human rights” with revisions made as early as the 1990s in a document loaded with this sort of phony rights creation, including the “rights” to protection, public service, social security, “holidays with pay,” food, clothing, housing, medical care, education and “necessary social services.” As discussed previously, the implementation of these, as has been done by governments in many different countries, is the formation of entitlement, and the destruction of true rights.

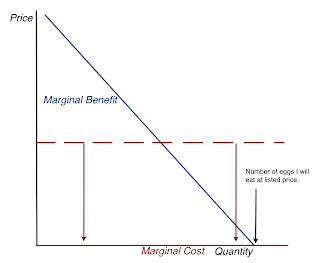

The logical follow-up question then, is “so what?” What difference does it make if people keep or lose the rights nature granted them? Consequences of the abolition of rights are many in number -- the simplest being that people tend to use their rights in a way that is productive and beneficial to themselves and others. Of all the basic facts discernible plainly by the way people act, it is that human beings are self-interested creatures. As described more accurately by economist Milton Friedman, co-founder of rational choice theory: “an individual acts as if balancing costs against benefits to arrive at action that maximizes personal advantage” (Friedman 15). People have an innate desire to obtain resources above and beyond those required to survive, which, as required by natural law, can only be initially obtained through the creation of wealth, i.e. the transformation of things from their natural state into one that is more useful to man. An example of this would be when construction workers and architects take lumber and brick -- resources that are relatively useless, in and of themselves -- to create a house that a family can live in and find useful. This sort of creation happens constantly between people, and can only ever be siphoned from by government.

Furthermore, people are interested in taking property they create and trading it with others voluntarily in win-win exchanges, which benefit both themselves and those they trade with. It stands to reason then, that the honest creation and exchange of property through voluntary means betters the lives of people, and should not be discouraged or made impossible.

Examples of these consequences to efficiency and production can be found in the current implementation of health care entitlement in the United States via the Affordable Care Act, better known as “Obamacare.” While it is true that a notable sum of previously-uninsured Americans is expected to benefit from access government healthcare (Cutler), provided the system remains functional, an analysis by Senators Tom Coburn and John Barrasso predicts a grim outcome. In particular, that “the overhaul will destroy a total of 120,000 to 700,000 jobs by 2019,” that it will “force industry leaders to curb the research and development of new medical tools,” and that it “creates a permanent disincentive against business growth” (Coburn). This occurs for a number of reasons. Firstly, as the government seizes the rightful property of taxpayers to provide for others’ healthcare, taxpayers become less willing to keep a job. After all, the workload of work remains the same, but now they’re keeping less of the money they make, thereby making government welfare options for the unemployed a more tempting substitute to holding a job. Secondly, the required increased taxation on business means that business owners are less willing, indeed less able, to initiate growth and development (Bowman). Just as there is a reduced incentive for people to stay employed, so is there a reduced incentive for people to hire, as the profit they make from their employees is significantly reduced. This leaves them with the options to either 1. pay their employees less, thereby tempting some to leave and cause the business to shrink, or 2. fire those employees who are no longer worth their revenue, thereby also reversing business growth. Should the business do neither, it will become unprofitable, and inevitably collapse to its competitors. Thirdly, mandating that employers provide healthcare services to their employees raises the cost of employing humans, causing workers whose jobs can also be accomplished by machinery to be laid off in favor of mechanical substitutes. This simultaneously raises both the rate of unemployment and the cost of doing business. From an economic perspective, the destruction of rights tends to follow the destruction of progress.

This same inefficiency is found in another form of rights violation seen today and throughout history, which is the prohibiting of sale for products deemed harmful by a given majority of people. For example, in the 1920s when the United States government upheld a prohibition of alcohol, illegal alcohol consumption became rampant, and drunkenness became more problematic than ever before. The desired effect of reducing alcohol supply was counterbalanced by a massive uprising of “speakeasies” -- illegal sellers of alcohol -- who reduced their costs by ignoring regulations and taxes. Likewise, the desired effect of reducing demand for alcohol was counterbalanced by a “forbidden fruit” effect, which increased the desire of some people to consume alcohol because it was forbidden (Miron).

Instead, the uncertainty of the alcohol illegally sold resulted in an increase in accidental poisonings. The lack of social controls and regulations led to an increase in patterns of binge drinking, as described by psychoanalyst Norman Zimberg who wrote: “People did not take the trouble to go to a speakeasy, present the password, and pay high prices for very poor quality alcohol simply to have a beer. When people went to speakeasies, they went to get drunk” (Zimberg 470). Since alcohol was sold in secretive environments, police were never notified by bartenders or customers during aggressive disputes, thereby raising the level of violent crime. Disrespect for the law saw dramatic increase, as people are more able to justify crime when they are already criminals, and the police force was made thoroughly busy arresting former-innocents who maintained the popular habit of drinking. As reported by economist Jeffery Miron, 7,000 arrests were made between the years 1921 and 1923 on the grounds of consumption or sale of alcohol, no doubt increasing costs of the police force, and further burdening the taxpayers (Miron).

The U.S. government’s current drug prohibitions have arguably shown many similar problems, including organized crime, mass arrest and imprisonment, drug abuse despite the law and a seemingly never-ending battle -- the “war on drugs” -- at an enormous expense. It is estimated that over 500,000 people are currently in prison for drug use, and that between $20 and $25 billion dollars per year have been spent over the last decade to fight drugs (Porter). This would likely explain a recent survey by economist Mark Thornton, which included hundreds of leading, modern economists and found that “most professional economists favored changes in public policy in the general direction of decriminalization [of drug use and sale]” (Thornton).

Another consequence of violating rights is that, by virtually all modern ethical standards, it’s an immoral thing to do, despite the failure of many to acknowledge when their rights are revoked. In 300 B.C. philosopher Epicurus described how "natural justice is a symbol or expression of usefullness, to prevent one person from harming or being harmed by another,” and in 20 A.D. the golden rule of Christ was composed, to “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Since the time of these statements people have, for the most part, accepted a non-aggression moral code. Generally speaking, people believe in the immorality of theft and assault, as is taught by every major religion and the majority of philosophers since ancient Greece. The problem is that many do not realize the immorality when rights are violated, mostly because they aren’t aware of when it occurs. No one has an issue with receiving benefits from government sources, and most have no problem with letting others receive them, but where the benefits come from is typically of little concern.

Particularly in the case of welfare, where material goods are given to the needy and the poor, support is often lent on ethical grounds, with the modest belief that helping those in need is a morally right action. As explained by political scientist Gregory Shaw, people support welfare policies through “the long-standing sense of obligation to help the poor among us—whether driven by guilt, the practical need to raise up the next generation of citizens, religious conviction, a strategy to placate the poor, or simply a near-universal sense of humanitarianism” (Shaw). Social theorist Michael B. Petersen has noted that people will support welfare policies based on “perceptions of the welfare recipients’ deservingness,” with support lent when the recipients are perceived as “unlucky” (Petersen). Unfortunately, what most don’t consider is how the material goods are obtained in the first place, which is, as I’ve explained previously, by the use of force. In essence, while people believe they are charitably helping the poor by supporting government welfare, in reality they are not. Such charity could be accomplished through personal, voluntary donation, or by the founding of a charitable organization, but welfare programs are the product of innocent people being forced to give away their property. Demanding that others lend help is not the same as lending help, nor is it truly humanitarian in any sense of the word.

So what does all of this mean, and what can be done about it? Currently the United States, viewed by many as one of the scarce few relatively-free countries left on Earth, is at a crucial tipping point in its history. Prominent public figures are often swaying public opinion to destroy the rights of some people in providing needs for others, disregarding the costs that entail and the problems that result. As a fellow citizen of the United States I urge that people everywhere stand up for true rights, and that they strive where they can to see through deception in the world of politics. I urge that they reject the notion that material goods, even when they are needed, be provided to others through entitlement, and instead that they look for ways to serve charitably, advocating for voluntary means of providing for the underprivileged. It is crucial that the United States citizenry vote for policies and representatives with these concepts in mind, that our country may keep the liberty it was established to maintain.

Works Cited

1. Coburn, Tom, and John Barrasso. "Health Care Reform Will Destroy Jobs." Health Care Legislation. Ed. David M. Haugen and Susan Musser. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2012. At Issue. Rpt. from "Grim Diagnosis: A Check-Up on the Federal Health Law." Oct. 2010. Gale Opposing Viewpoints In Context. Web. 8 Nov. 2012.

2. Cutler, David, and Neeraj Sood. "Health Care Reform Will Create New Jobs." Health Care Legislation. Ed. David M. Haugen and Susan Musser. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2012. At Issue. Rpt. from "New Jobs Through Better Health Care: Health Care Reform Could Boost Employment by 250,000-400,000 a Year this Decade." Center for American Progress, 2010. Gale Opposing Viewpoints In Context. Web. 8 Nov. 2012.

3. Petersen, Michael B. "Deservingness versus Values in Public Opinion on Welfare: The Automaticity of the Deservingness Heuristic | Michael Bang Petersen – Academia.edu." Deservingness versus Values in Public Opinion on Welfare: The Automaticity of the Deservingness Heuristic | Michael Bang Petersen - Academia.edu. Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, Denmark, Jan. 2011. Web. 8 Nov. 2012.

4. Shaw, Greg M. "Changes in Public Opinion and the American Welfare State (Report)."Business Information, News, and Reports. Illinois Wesleyan University, 2009. Web. 8 Nov. 2012.

5. Thornton, Mark. "AMERICAN Economic Association." Ebscohost. AMERICAN Economic Association, 2007. Web. 8 Nov. 2012.

6. Bowman, Scott A. "Should I Stay or Should I Go? Tax Considerations in U.S. Expatriation." Ebscohost. American Bar Association, Oct. 2012. Web. Nov. 12.

7. Friedman, Milton. Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1953. Print.

8. Miron, Jeffery A. "Alcohol Prohibition." Economic History Services. Economic History Association, 1 Feb. 2010. Web. 27 Nov. 2012.

9. Zimberg, Norman E., Nancy K. Mello, and Jack H. Mendelson. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcoholism. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979. Print.

10. Porter, Eduardo. “Numbers Tell Failure in Drug War.” New York Times 4 Jul. 2012: B1. New York Times. Web. 27 Nov. 2012.